SUBHEAD: The stockpile of virtual assets that many of us relied on drawing down during retirement is already losing value; that process will accelerate.

By André Angelantoni on 7 January 2010 in Transition Times -

(http://transition-times.com/2010/01/07/the-end-of-retirement)

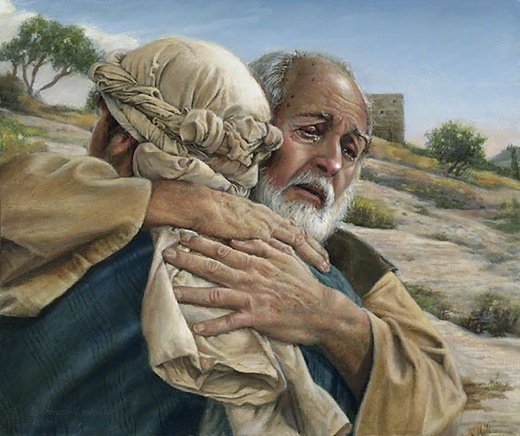

Image above: "The Prodigal Son" by Liz Lemon Swindle. From http://www.freespiritart.com/swindle-art-prodigal-son.php

By André Angelantoni on 7 January 2010 in Transition Times -

(http://transition-times.com/2010/01/07/the-end-of-retirement)

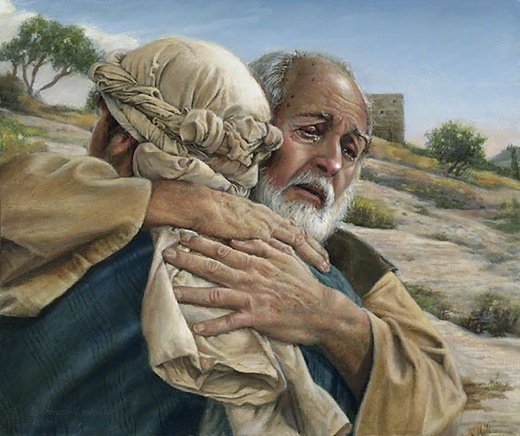

Image above: "The Prodigal Son" by Liz Lemon Swindle. From http://www.freespiritart.com/swindle-art-prodigal-son.php

“When do I call my children home?”

My friend asked me that question two years ago after I gave him a thorough explanation of what the decline of oil production meant for our civilization. Like many modern parents, his children were spread around the continent, or traveling the world, and he could instantly see how important his family working together was going to be in the future.

His question is a very good one and represents one way we might all want to consider relating to The Long Descent.

Before discussing that, a small detour is in order. I’ve used John Michael Greer’s label “The Long Descent” for this essay to make a point. In his book by the same name, Greer describes how civilizations tend to take decades if not centuries to descend from the pinnacle of their size to the point the last cities are abandoned to the jungle (in the case of the Mayans).

Greer convincingly uses history to show that civilizations rarely if ever end by a catastrophic and instant collapse of all their systems at the same time. Instead, they experience mini-collapses followed by stasis or even some recovery. After reading his theory of catabolic collapse, I’ve modified my Staircase Model to include more steps after the big step in the middle:

Though Greer and I are now aligned on the likely way our civilization will decline as we lose access to energy-dense fossil fuels, Greer’s especially is the long view. He is looking out tens and possibly hundreds of generations. With this long timescale, there is a danger in allowing the term “The Long Descent” to lull us into thinking we have more time than we do for certain preparations. This would be unfortunate because we have several challenges that won’t take generations to arrive. One significant and early challenge is already upon us.

The End of Retirement

Only 120 years old and widely available to the middle class for just the last 60 or so years, retirement is coming to an end. It is the unique product of several converging factors. The first was energy abundance in the form of fossil fuels, which allowed an ever-decreasing number of people to work the land to produce food for those that lived in the cities. Elevating great numbers of people above the daily grind of subsistence farming was necessary before the next factor could arise.

The second factor was the creation of a financial system that enabled us to “bank” future personal resource exploitation in the form of money. Online retirement calculators tell us how much money we need to retire but that money is clearly a proxy for the world’s resources. It would be impractical for the calculator to advise us to stockpile “2000 board-feet of wood for a new house, 20 lb of uranium for electricity and 400 gallons of jet fuel for foreign vacations.”

Instead, it tells us to store money that we will in the future convert to resources. Once we have a nice stockpile of dollars or euros, the idea is to draw it down by converting it to foreign vacations (which are energy hogs, using in one or two weeks the amount of energy used by someone traveling by car for an entire year — simply because the destinations are often thousands of miles away), nice dinners (which bring an astonishing array of foods from around the world to an area no bigger than a dinner plate) and the occasional financial bailout of one’s children when they run out of money on a round-the-world trip.

Both of these factors are in the process of disappearing. We are not experiencing the popping of a short-term economic bubble like the tech boom or the tulip mania of several centuries ago. After this popping, there will be no significant recovery.

We now can see that the entire economy is a giant bubble that was inflated when we discovered the fossil fuel energy jackpot. Had we not found these fuels, world economic growth would surely have slowed or even reversed when we began to run out of trees to cut down some 200 years ago. (I show in my video “Preparing for a Post Peak Life” why renewable energy sources can’t even begin to make up for the loss of fossil fuels and especially oil; I won’t go into it here.)

To permit the economic bubble to expand at will, we severed the connection between money and the physical world. Money today has no physical backing. I can’t go to the issuer of the the U.S. dollar, the United States government, and trade it for gold, or silver or even beans. Without the anchoring constraint of tying paper currencies to the physical world, all forms of virtual wealth, of which money is just one form, have been allowed to increase beyond imagination. The hundreds of trillions in derivatives are the culmination of this process.

We now find that there is currently more money in existence than the world’s resources can support — especially oil. Oil is particularly important because as a fantastically energy dense and portable energy source it is what I call an “enabling resource.”

In other words, it enables us to get all the other resources upon which we depend. True, we could over time switch to electricity powered by wind or coal, but many societal functions become more expensive, more time consuming and often impossible. For instance, mining an important mineral in a remote location is significantly more difficult if instead of simply transporting the energy to run the mining equipment by tanker truck the mining company has to run long distance electric wires or set up a small coal-fired electric plant. Portable, liquid fuel has allowed and accelerated our growth, and the impact has been like a cannon ball shot from a cannon.

Jeffrey Brown, who is a colleague and tireless educator on the matter of declining net oil exports, points out the connection between oil and money by asking this incisive question:

“What value do the ten largest banks in the world have if we take away the ten largest oil fields?”

The answer of course is “almost nothing.” Without energy, the money controlled or lent by the banks literally wouldn’t be able to do anything, including creating profit. Take away energy, world economic growth reverses and the value we’ve assigned in the current system (i.e. stock prices, future pension obligations, etc.) dramatically drops in value.

What does this mean for the relatively short-lived phenomenon of retirement? It means that whatever virtual assets you have accumulated over a lifetime of work — the money, stocks, bonds, real estate and the pensions made of those financial instruments — are headed for a massive devaluation.

There are several ways it could happen. In response to the end of growth and with no physical constraint on printing money (because the link to the physical world is now gone) governments might hyperinflate their currencies as they struggle with debt they can no longer pay back.

They should actually be doing exactly the opposite: the should remove money as the world economy contracts to return a balance between money and the resources implicitly backing the money. Alternatively, we could experience a fiat currency collapse, or bank runs, or a plunge in the stock market when one day a large enough group of people loses confidence in the system. Any one of those events could trigger the big step shown in the Staircase Model.

However the method, the devaluation must happen as energy is removed from the world economy. If you can’t yet see what I’m pointing to, keep pondering Jeffrey’s question as you move through the world. See how energy, particularly oil, is used to manufacture and transport every good and provide every service. Then take away the energy or make it very, very expensive. Does the economy expand or contract? Do assets increase in value or decrease in value? Which ones? Eventually you will see the connection between oil and money. As oil goes, so does money — and your retirement assets.

Is there still some time before this devaluation occurs? Yes, but just how long is impossible to predict with accuracy. Personally, I can’t see the system holding up much beyond this decade (i.e. up to 2020), but reasonable, intelligent people will provide different answers to this question.

Turning Virtual Assets to Real Assets

The stockpile of virtual assets that many of us relied on drawing down during retirement is already losing value; that process will accelerate. It’s time to put that value to use before it disappears entirely.

In my courses the hardest thing for people to do is act on this insight, for many reasons. It might mean giving up on dreams of endless travel and golf games. It might mean their children do not go to college. It definitely means preparing for a very different life. Regardless of the reason, I always encourage people to summon the courage to act. In particular, I recommend that people start converting their virtual assets to real assets (i.e. physical things) while the virtual assets still have value. Timing these conversions well means getting more real assets in exchange for the virtual assets but how long to wait before one is mostly out of the virtual asset game is a matter of personal tolerance for risk.

It takes time to get ready for the end of retirement. Products that are easy to obtain now will be difficult or impossible to obtain outside of the black market (if at all). There are new skills to learn, like learning to grow food, or some other skill that can be traded for food. Homes need to be retrofitted to use the least possible energy and, where there is sufficient money, to produce energy. Then there is the very real challenge of being set up properly to pay property taxes and possibly a mortgage year after year (or the rent, if one doesn’t own one’s shelter). Families will do better if their members live close to each other and especially in the same house to help pay for common expenses. I know of several families making plans to move close to each other right now.

After a close look, most people eventually see that they are perfectly capable of running a post peak household once the need for iPods and foreign vacations goes away. But that doesn’t mean that setting up for The Long Descent can be done overnight. I would say a full third of the people in my courses have already been diligently at work for years.

If Iraqi oil buys us a few more years, we should count ourselves lucky but it is far from guaranteed that Iraqi oil will come online quickly enough and in sufficient quantity to make a significant difference. In other words, don’t put off preparing or — even worse — think The Long Descent has been avoided. This is especially true if you see yourself, as my friend does, one day calling your children, taking a deep breath and quietly but purposefully saying, “I think it’s time for you to come home.”

My friend asked me that question two years ago after I gave him a thorough explanation of what the decline of oil production meant for our civilization. Like many modern parents, his children were spread around the continent, or traveling the world, and he could instantly see how important his family working together was going to be in the future.

His question is a very good one and represents one way we might all want to consider relating to The Long Descent.

Before discussing that, a small detour is in order. I’ve used John Michael Greer’s label “The Long Descent” for this essay to make a point. In his book by the same name, Greer describes how civilizations tend to take decades if not centuries to descend from the pinnacle of their size to the point the last cities are abandoned to the jungle (in the case of the Mayans).

Greer convincingly uses history to show that civilizations rarely if ever end by a catastrophic and instant collapse of all their systems at the same time. Instead, they experience mini-collapses followed by stasis or even some recovery. After reading his theory of catabolic collapse, I’ve modified my Staircase Model to include more steps after the big step in the middle:

Though Greer and I are now aligned on the likely way our civilization will decline as we lose access to energy-dense fossil fuels, Greer’s especially is the long view. He is looking out tens and possibly hundreds of generations. With this long timescale, there is a danger in allowing the term “The Long Descent” to lull us into thinking we have more time than we do for certain preparations. This would be unfortunate because we have several challenges that won’t take generations to arrive. One significant and early challenge is already upon us.

The End of Retirement

Only 120 years old and widely available to the middle class for just the last 60 or so years, retirement is coming to an end. It is the unique product of several converging factors. The first was energy abundance in the form of fossil fuels, which allowed an ever-decreasing number of people to work the land to produce food for those that lived in the cities. Elevating great numbers of people above the daily grind of subsistence farming was necessary before the next factor could arise.

The second factor was the creation of a financial system that enabled us to “bank” future personal resource exploitation in the form of money. Online retirement calculators tell us how much money we need to retire but that money is clearly a proxy for the world’s resources. It would be impractical for the calculator to advise us to stockpile “2000 board-feet of wood for a new house, 20 lb of uranium for electricity and 400 gallons of jet fuel for foreign vacations.”

Instead, it tells us to store money that we will in the future convert to resources. Once we have a nice stockpile of dollars or euros, the idea is to draw it down by converting it to foreign vacations (which are energy hogs, using in one or two weeks the amount of energy used by someone traveling by car for an entire year — simply because the destinations are often thousands of miles away), nice dinners (which bring an astonishing array of foods from around the world to an area no bigger than a dinner plate) and the occasional financial bailout of one’s children when they run out of money on a round-the-world trip.

Both of these factors are in the process of disappearing. We are not experiencing the popping of a short-term economic bubble like the tech boom or the tulip mania of several centuries ago. After this popping, there will be no significant recovery.

We now can see that the entire economy is a giant bubble that was inflated when we discovered the fossil fuel energy jackpot. Had we not found these fuels, world economic growth would surely have slowed or even reversed when we began to run out of trees to cut down some 200 years ago. (I show in my video “Preparing for a Post Peak Life” why renewable energy sources can’t even begin to make up for the loss of fossil fuels and especially oil; I won’t go into it here.)

To permit the economic bubble to expand at will, we severed the connection between money and the physical world. Money today has no physical backing. I can’t go to the issuer of the the U.S. dollar, the United States government, and trade it for gold, or silver or even beans. Without the anchoring constraint of tying paper currencies to the physical world, all forms of virtual wealth, of which money is just one form, have been allowed to increase beyond imagination. The hundreds of trillions in derivatives are the culmination of this process.

We now find that there is currently more money in existence than the world’s resources can support — especially oil. Oil is particularly important because as a fantastically energy dense and portable energy source it is what I call an “enabling resource.”

In other words, it enables us to get all the other resources upon which we depend. True, we could over time switch to electricity powered by wind or coal, but many societal functions become more expensive, more time consuming and often impossible. For instance, mining an important mineral in a remote location is significantly more difficult if instead of simply transporting the energy to run the mining equipment by tanker truck the mining company has to run long distance electric wires or set up a small coal-fired electric plant. Portable, liquid fuel has allowed and accelerated our growth, and the impact has been like a cannon ball shot from a cannon.

Jeffrey Brown, who is a colleague and tireless educator on the matter of declining net oil exports, points out the connection between oil and money by asking this incisive question:

“What value do the ten largest banks in the world have if we take away the ten largest oil fields?”

The answer of course is “almost nothing.” Without energy, the money controlled or lent by the banks literally wouldn’t be able to do anything, including creating profit. Take away energy, world economic growth reverses and the value we’ve assigned in the current system (i.e. stock prices, future pension obligations, etc.) dramatically drops in value.

What does this mean for the relatively short-lived phenomenon of retirement? It means that whatever virtual assets you have accumulated over a lifetime of work — the money, stocks, bonds, real estate and the pensions made of those financial instruments — are headed for a massive devaluation.

There are several ways it could happen. In response to the end of growth and with no physical constraint on printing money (because the link to the physical world is now gone) governments might hyperinflate their currencies as they struggle with debt they can no longer pay back.

They should actually be doing exactly the opposite: the should remove money as the world economy contracts to return a balance between money and the resources implicitly backing the money. Alternatively, we could experience a fiat currency collapse, or bank runs, or a plunge in the stock market when one day a large enough group of people loses confidence in the system. Any one of those events could trigger the big step shown in the Staircase Model.

However the method, the devaluation must happen as energy is removed from the world economy. If you can’t yet see what I’m pointing to, keep pondering Jeffrey’s question as you move through the world. See how energy, particularly oil, is used to manufacture and transport every good and provide every service. Then take away the energy or make it very, very expensive. Does the economy expand or contract? Do assets increase in value or decrease in value? Which ones? Eventually you will see the connection between oil and money. As oil goes, so does money — and your retirement assets.

Is there still some time before this devaluation occurs? Yes, but just how long is impossible to predict with accuracy. Personally, I can’t see the system holding up much beyond this decade (i.e. up to 2020), but reasonable, intelligent people will provide different answers to this question.

Turning Virtual Assets to Real Assets

The stockpile of virtual assets that many of us relied on drawing down during retirement is already losing value; that process will accelerate. It’s time to put that value to use before it disappears entirely.

In my courses the hardest thing for people to do is act on this insight, for many reasons. It might mean giving up on dreams of endless travel and golf games. It might mean their children do not go to college. It definitely means preparing for a very different life. Regardless of the reason, I always encourage people to summon the courage to act. In particular, I recommend that people start converting their virtual assets to real assets (i.e. physical things) while the virtual assets still have value. Timing these conversions well means getting more real assets in exchange for the virtual assets but how long to wait before one is mostly out of the virtual asset game is a matter of personal tolerance for risk.

It takes time to get ready for the end of retirement. Products that are easy to obtain now will be difficult or impossible to obtain outside of the black market (if at all). There are new skills to learn, like learning to grow food, or some other skill that can be traded for food. Homes need to be retrofitted to use the least possible energy and, where there is sufficient money, to produce energy. Then there is the very real challenge of being set up properly to pay property taxes and possibly a mortgage year after year (or the rent, if one doesn’t own one’s shelter). Families will do better if their members live close to each other and especially in the same house to help pay for common expenses. I know of several families making plans to move close to each other right now.

After a close look, most people eventually see that they are perfectly capable of running a post peak household once the need for iPods and foreign vacations goes away. But that doesn’t mean that setting up for The Long Descent can be done overnight. I would say a full third of the people in my courses have already been diligently at work for years.

If Iraqi oil buys us a few more years, we should count ourselves lucky but it is far from guaranteed that Iraqi oil will come online quickly enough and in sufficient quantity to make a significant difference. In other words, don’t put off preparing or — even worse — think The Long Descent has been avoided. This is especially true if you see yourself, as my friend does, one day calling your children, taking a deep breath and quietly but purposefully saying, “I think it’s time for you to come home.”

No comments :

Post a Comment